Bernhard

Münzenmayer-Stipanits

is reading Ulysses

EPISODE 1

‘Ulysses’ starts at the top of the Sandycove Martello tower overlooking Dublin Bay, where Stephen Dedalus, a young man of letters to be, is staying with his friend Buck Mulligan. Buck is having a shave while the two are discussing their strained relationship. We then see them at breakfast, together with Haines, an Englishman, whom Stephen heartily dislikes. At the end of a walk to the shore, Stephen decides not to return to the tower in the evening.

There is not much of a plot, but through the dialogues and insights on Stephen’s thoughts we get an idea of his complex personality as much as his rather sombre views on the world and on himself.

In this early stage, I simply transferred my sketches onto the stone without altering them very much and even emphasized a certain crudeness, especially in the lettering of the text passages.

While this may be showing how much the project as well as my relationship with the book were still at their beginning, my choice of colour, which could be described as “snotgreen and alike” reflects how I imagined a world seen through Steven’s eyes.

EPISODE 2

Stephen earns his money working at a boys’ school. As he is teaching history to a group of students, there is no connection to be felt between him and them. They seem to exist on different planes.

To visualize this, I introduced mirror writing for parts of the text elements and continued to use this not only to deal with the “stream of consciousness” which dominates large parts of the novel, but also to indicate different layers of narration.

Later, Stephen collects his pay from the headmaster Mr. Deasy, who reveals himself to be a unionist and antisemite. Knowing about Stephen’s connections to the press, Deasy asks him to get a letter of his, really a political pamphlet, printed. Despite their different positions on most topics, he seems to appreciate Stephen, who, for his part, refuses to return this sympathy and is happy to leave.

When I read imagining Jews at the Paris stock exchange, condemned to failure and restlessness, I saw a Jewish cemetery like the ones still to be found in different places across Europe. There is only a loose connection between the two images, which, by the way, is completely normal: We all connect our own images with what we are reading. In this case, I decided to replace Stephen’s with mine. In fact, print 26 with its text interspersed with chaotically arranged gravestones is really a synthesis of both views: Stephen’s, written, and mine, drawn.

EPISODE 3

As Stephen is walking along Sandymount Beach, his mind roams: Starting with Aristotle’s theory of perception, human conception, a visit at his aunt who lives nearby, and memories of his family and his youth, he arrives at the time he spent in Paris, which was interrupted by his mother’s death.

From these interior, partly quite abstract matters, Stephen’s focus slowly shifts to the here and now: a strolling dog sniffing the carcass of a dead dog, which reminds Stephan of a drowned man floating somewhere in the bay. A pair of cockle pickers, the woman inspiring erotic thoughts. The rocks, the sand, the drifts and currents, light on the water, a ship sailing by.

My episode 3 opens with an exasperated scribble I made after reading the opening lines for the third time. I suspect Joyce intended this at least as a side effect. Things get better with clearer situations, figures and silhouettes evolving. Some of these appear as negatives as in print 35, which draws from arts history, 44, inspired by Richard Head’s poem “The Rogue’s Delight” *, or 48. Generally, in this episode, I was glad when things moved to a more material sphere and got easier to translate into pictures, which, in this case, I happily accepted, albeit still in a reduced, abstracted form.

*I looked up the lines quoted by Stephen years after I had made the print and was surprised at how accurate my intuitive interpretation had been.

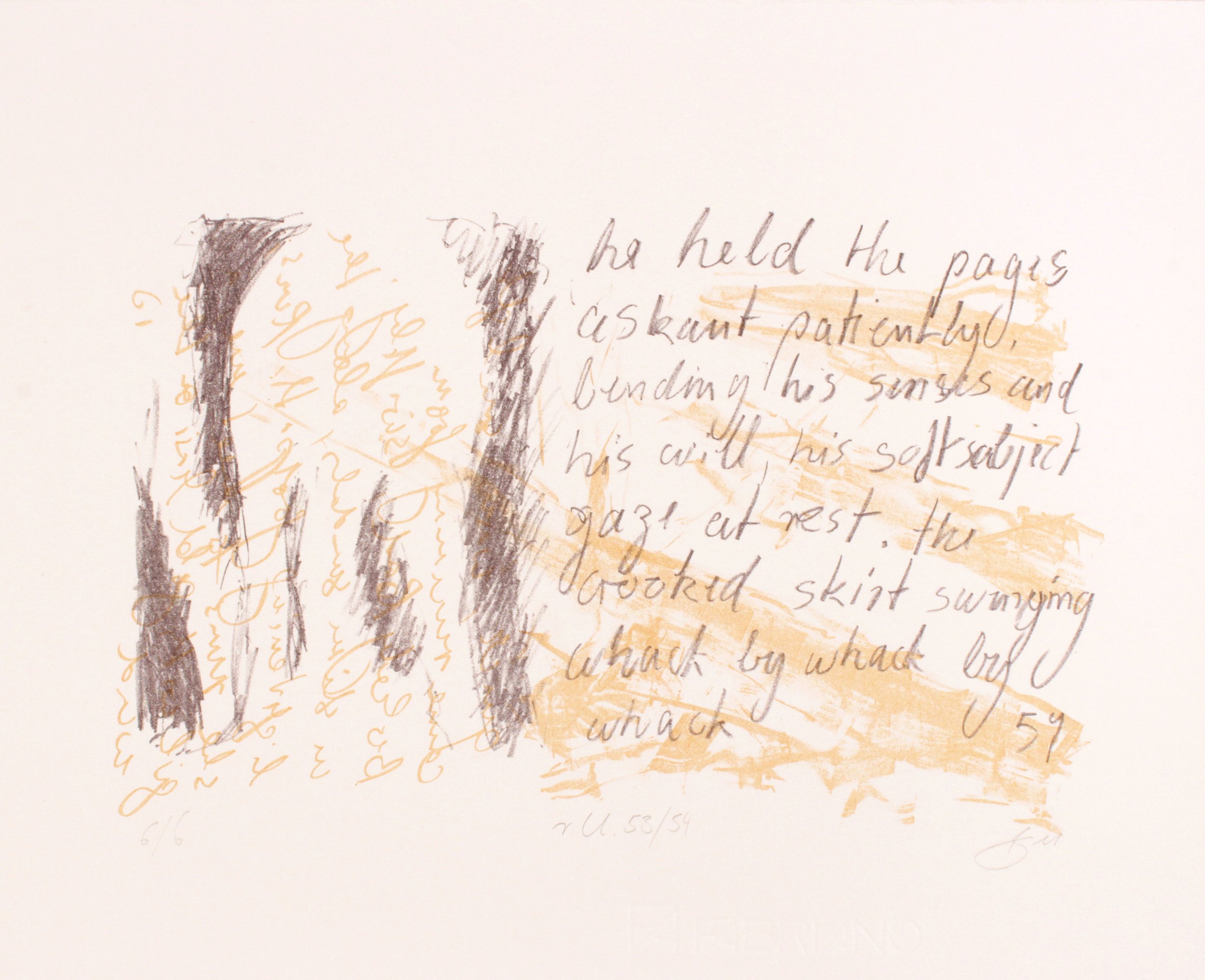

EPISODE 4

As Leopold Bloom, the other main character of ‚Ulysses‘, and his wife Molly, a singer, have breakfast, we learn about the day ahead: Bloom has a funeral to attend, Molly will receive the visit of Blazes Boylan, her manager and, presumably, lover. The tone between them suggests marital familiarity; yet both seem to be conscious of the issues not talked about. After breakfast, Bloom reads a letter from their daughter Milly, then, having relieved himself at the outhouse (toilet), leaves for town.

The story now moves into a more down-to-earth sphere, and so do my pictures, which, with a few exceptions, reflect Bloom’s also much more physical, ordinary, at times even vulgar view of things. Otherwise, there is no great change of style happening in this episode, as I was still following the original sketches rather closely. A few prints (50, 55, 61), however, show the beginning of a development towards a more conscious and deliberate design of text elements. Announcing itself only timidly here, this is going to gain importance later on.

EPISODE 5

At the post-office, Bloom anonymously collects a letter from a lady friend with whom he is entertaining an erotic correspondence, but he can read it only after he has shaken off a loquacious acquaintance. Before the funeral, Bloom has time to fill, so he enters a church, listens to Mass for a while, orders a lotion for Molly at the chemists, and goes to take a bath.

Episode 5 shows Bloom as an attentive observer with a restless mind, always ready to take things in and add them to the images and concepts his head is already overflowing with.

Some images were easy to translate or sprang to my mind spontaneously: Marching soldiers as Bloom reflects on the state of the British army (66), flowers and phallic forms as he recalls Martha’s letter (70), a 17th century still life with Martha and Maria in the background (71), a swirling flood of brown liquid (73), or the grid of a confessional (78). Others, stimulated by sensations rather than concrete images had to remain in the abstract (71, 74, 77). Some again, I had literally before my eyes while I was reading: The church interior (75) originates from a photograph I was using as a bookmark.

EPISODE 6

On the journey to the funeral of Patrick Dignam, died of a stroke, Bloom shares a carriage with three gentlemen. While Bloom eagerly tries to take part in the small talk typical among people who know each other without being friends, his thoughts stray to the premature death of his son and the suicide of his father. At the cemetery, he contemplates various aspects of death in a more neutral way and with a considerable distance to what is happening around him.

Though this is never openly expressed, Bloom perceivably occupies an inferior position among the men attending the funeral, placed, at best, at the fringe of the group.

Differing in style and degree of abstraction, the pictures connected with this episode share an underlying subdued mood. To me, some of them are like film shots with little or no movement, viewed from a slowly moving carriage, or seen as if happening in slow motion, from a distance, which is how I imagine Bloom experiencing the funeral. Much more concrete, perhaps even real, is what appears before his inner eye.

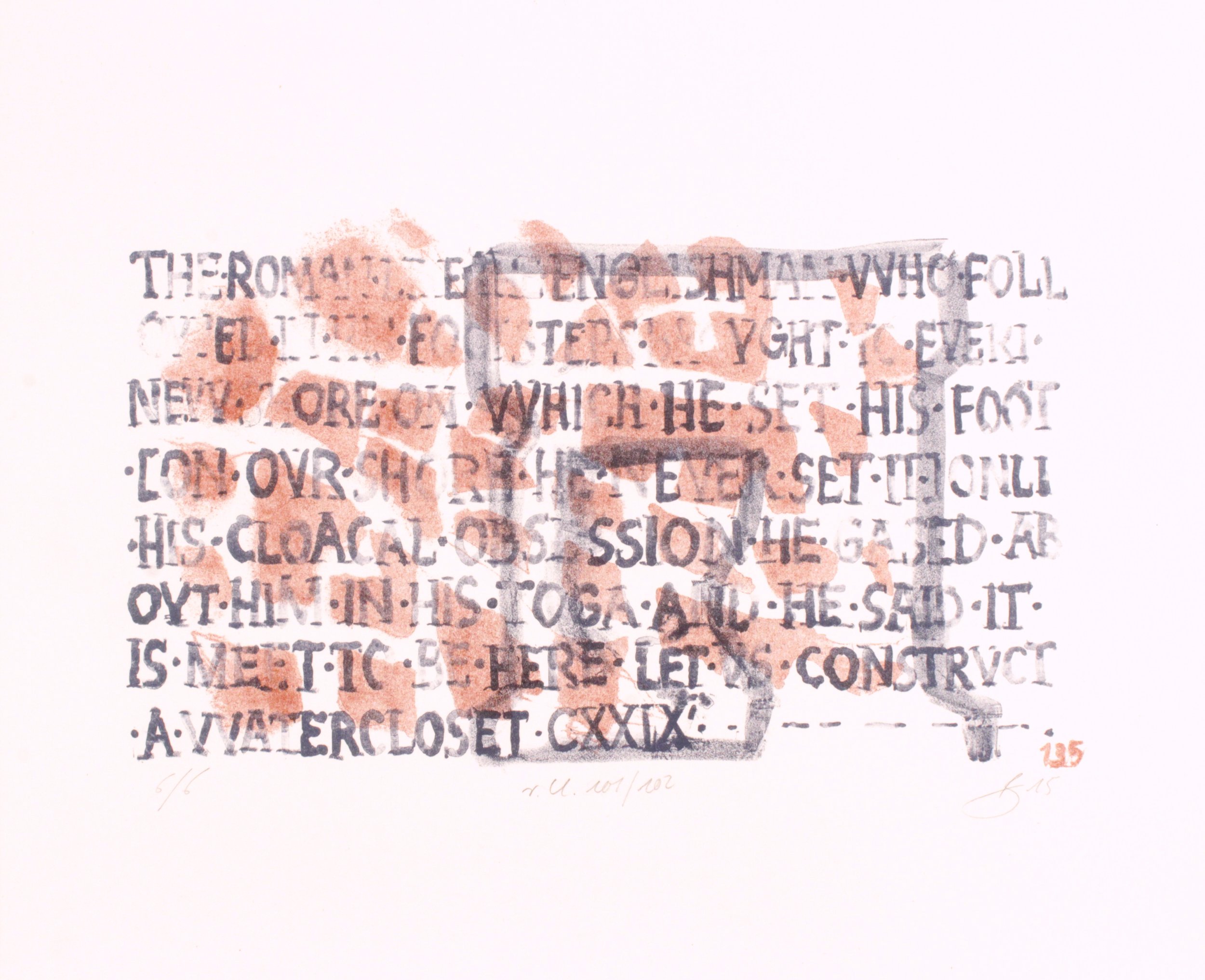

EPISODE 7

At the Freeman’s journal, Bloom goes about his unrewarding job as a canvasser, while Stephen, wo arrives to deliver Deasy’s letter, is flattered by the gathered editors as a promising young writer. The episode is characterized by a lot of idle talk touching all kinds of cultural and historical topics, especially the Invincibles and the Phoenix Park murders of 1882. Stephen contributes a somewhat nonsensical anecdote about two old Dublin ladies.

Like the headlined paragraphs dividing the episode, each picture highlights a specific situation, image or thought. Rather than following and illustrating the course of events, I preferred to meet Joyce’s numerous references with my own connotations, as, for instance, in print 101, a clumsily written Roman “Capitalis monumentalis” script to illustrate Professor MacHugh’s interpretation of Roman history, or, in print 105, the image of a flight of starlings driven by a storm, to which the souls are compared in the 5th chant of Dante’s Inferno quoted by Stephen.

EPISODE 8

While the episode is generally considered to be dominated by the subject of food, which indeed shines through at every corner as Bloom is followed on his way to lunch and further on, my pictures focus on things he sees or which are happening to him along this way, and, of course, the thoughts and feelings they arouse:

So, Shakespeare (110) is followed by the gulls on the Liffey (111), the meeting of an old acquaintance (114) and views on the press (115).

Bloom’s thoughts about Irish conspiratorial circles (117) made me think of the 1916 Easter Rising, which is why I used a photograph of Countess Markiewicz, one of the insurgents, in prison.

Uncomfortable thoughts about Molly and Boylan remain in the abstract and atmospheric (119, 122), while reflections on vegetarianism and its opposite (120) invited a more graphic illustration.

123, 125, 126, and 127 are dedicated to sensuality in different forms.

128, at last, illustrates a scene.

EPISODE 9

This chapter presents Stephen discussing his Shakespeare/Hamlet-theory with the learned, and, of course, this is as much about Stephen as it is about the poet and his works. Bloom has a cameo in the episode, but not in my drawings. Buck Mulligan has, with one quotation.

Stephen’s wrestling with Shakespeare, himself, his family, and the world inspired a rawness of style on my part, later a desire to dissociate myself from the maze of his thoughts and replace his images with my own, which may explain some of the seemingly absurd combinations of image and text at the end of the episode.

So, these could be subtitles for some of the pictures:

130: Raw typography for a masked flourish.

133: About mothers and deathbeds.

134: Fields waving, murmuring.

135: Adultery as I imagine Peter Greenaway could have imagined it.

136: Getting stuck in the text I replaced what I read with myself reading.

137: Belief – unbelief: This statue of Saint Michael at the entrance of a gothic church seemed fitting.

138: Angus, soaring.

139: Archaic.

EPISODE 10

In a sequence of scenes different people move through town. Meeting or just crossing each other, sometimes communicating, they go about their lives. Seemingly unconnected, these scenes discretely help the story to move forward. But they are more than stones of a mosaic which will fall into place later; every one of them is a miniature in its own right. Remaining rather close to the text with my illustrations most of the time, I only took the liberty of replacing a Dublin suburban landscape with a Lower Austrian one in print 141 and supplementing the fire of Cashel Cathedral in 144 with an indignant sculpted lady from Mount Cashel.

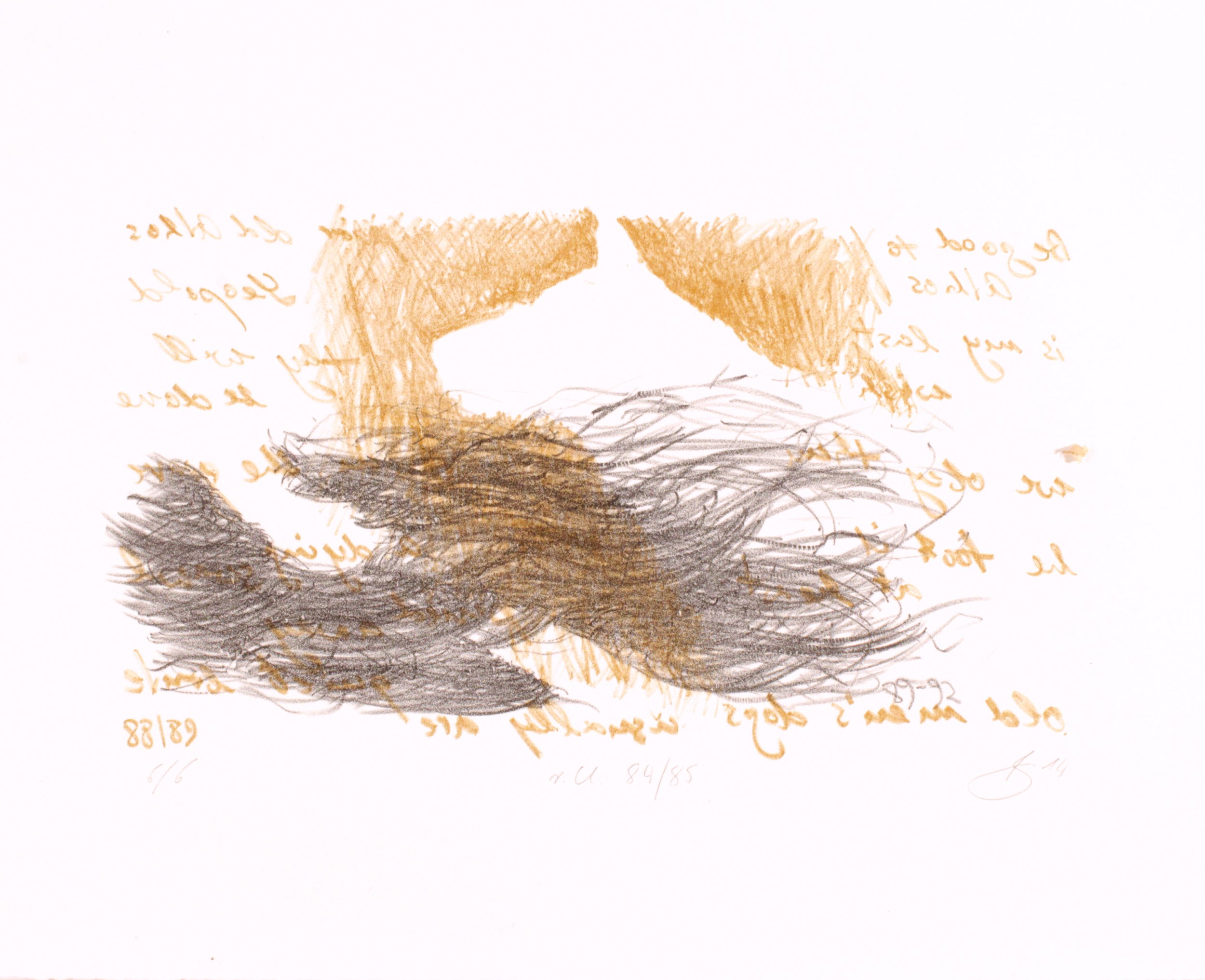

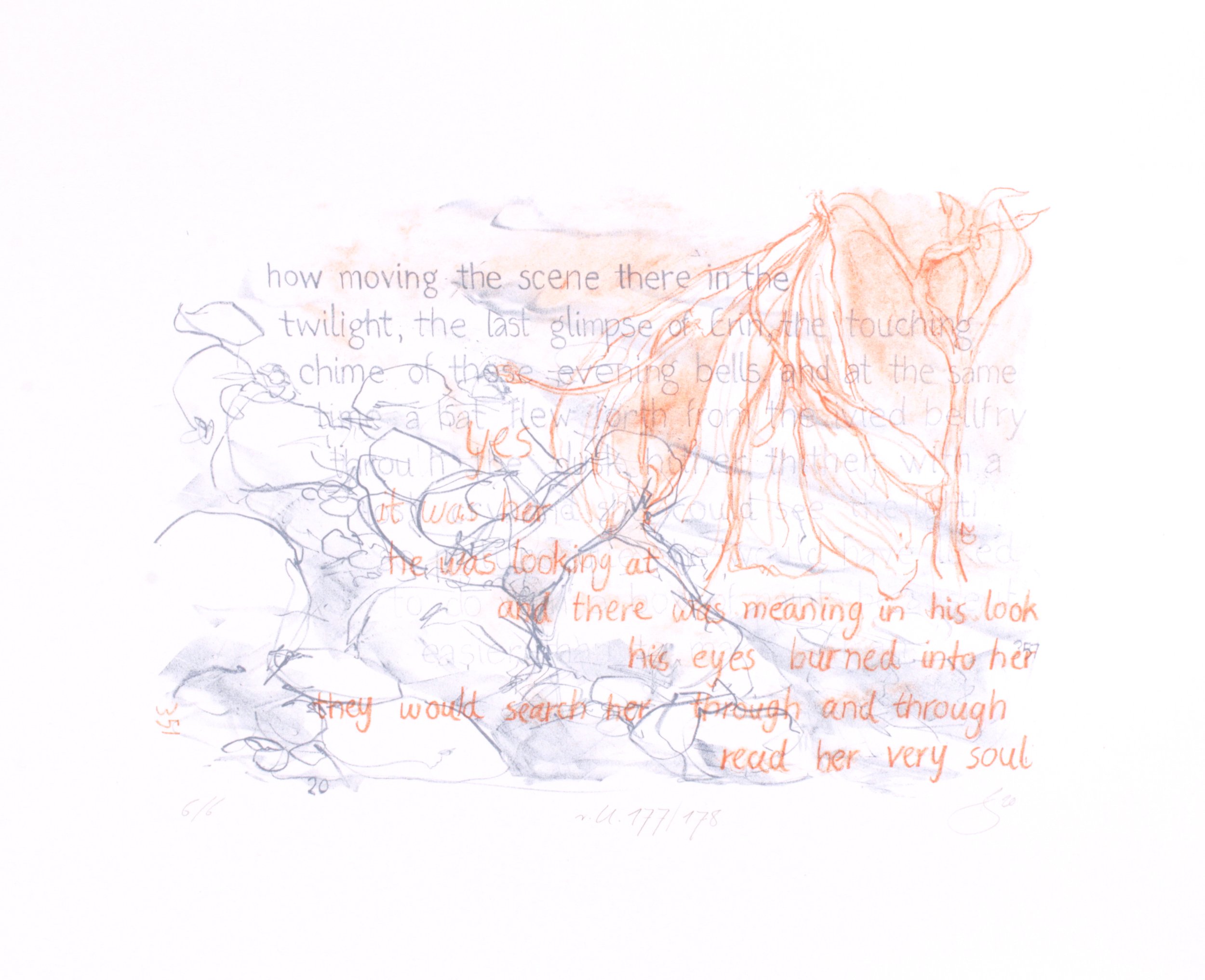

EPISODE 11

Paths cross at the Ormond Hotel in the afternoon, and almost everybody seems to be meeting there. A lot of things happen simultaneously and are described in a kaleidoscope of activities, thoughts, sounds and sensations. The language switches between prose and what could pass as Dadaist poetry – except that it is most probably thoroughly composed.

It is mainly this experimental language which influenced my pictures. Except perhaps print 152, they have little to do with the events of the episode but rather stay on the abstract side.

EPISODE 12

In a pub, Bloom is now openly confronted with the antisemitism which has been hinted at before, personified here by the Citizen, an Irish nationalist. The episode is told in a continous change between the colloquial language of a first-person narrator and parodies of different literary styles.

For the “slang”-part of the text, the Citizen’s dog Garyowen offered itself as a symbol of the general atmosphere and so appears in various forms and numbers, alternating with some of the more graphic illustrations of the series. The dominant colours are hues of red and orange.

For the “literary” half, which starts alluding to Irish mythology and refers to mystifications of all kinds, I used a special script: Insular majuscule, known from illuminated manuscripts like the Book of Kells. Nowadays, it frequently marks things as “Celtic”, but also appears in various esoteric contexts. As colours for these prints, I chose different shades of greens and blues.

There is one exception, print 171, which I wanted to stand out for the simple reason that “Love loves to love love” is one of my favourite lines.

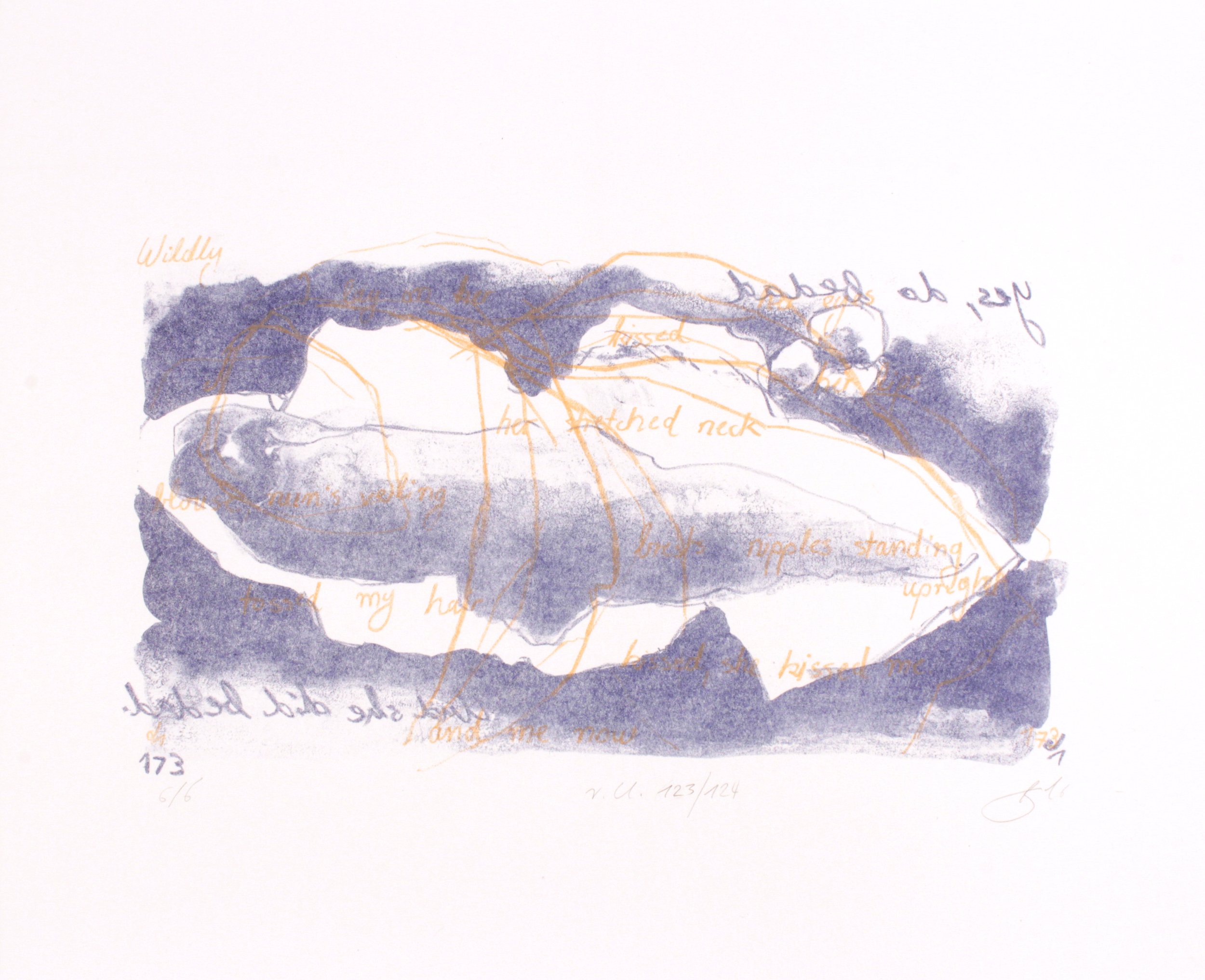

EPISODE 13

On Sandymount Strand, Gerty McDowell, a young lady following her phantasies notices a gentleman watching her from a distance. Their eye-contact develops into mutual excitement, followed by a sobering anti-climax as the man – Bloom – sees her limping away.

Lilies, traditionally associated with purity and innocence are amazingly sensuous flowers at a closer look. Executed in tones of yellow, mauve and red, they proved an ideal representation of Gerty. Drawings of sticks and stones from a riverbank, printed in blues and greys, serve as a contrast and help to evoke the atmosphere of a beach in the evening.

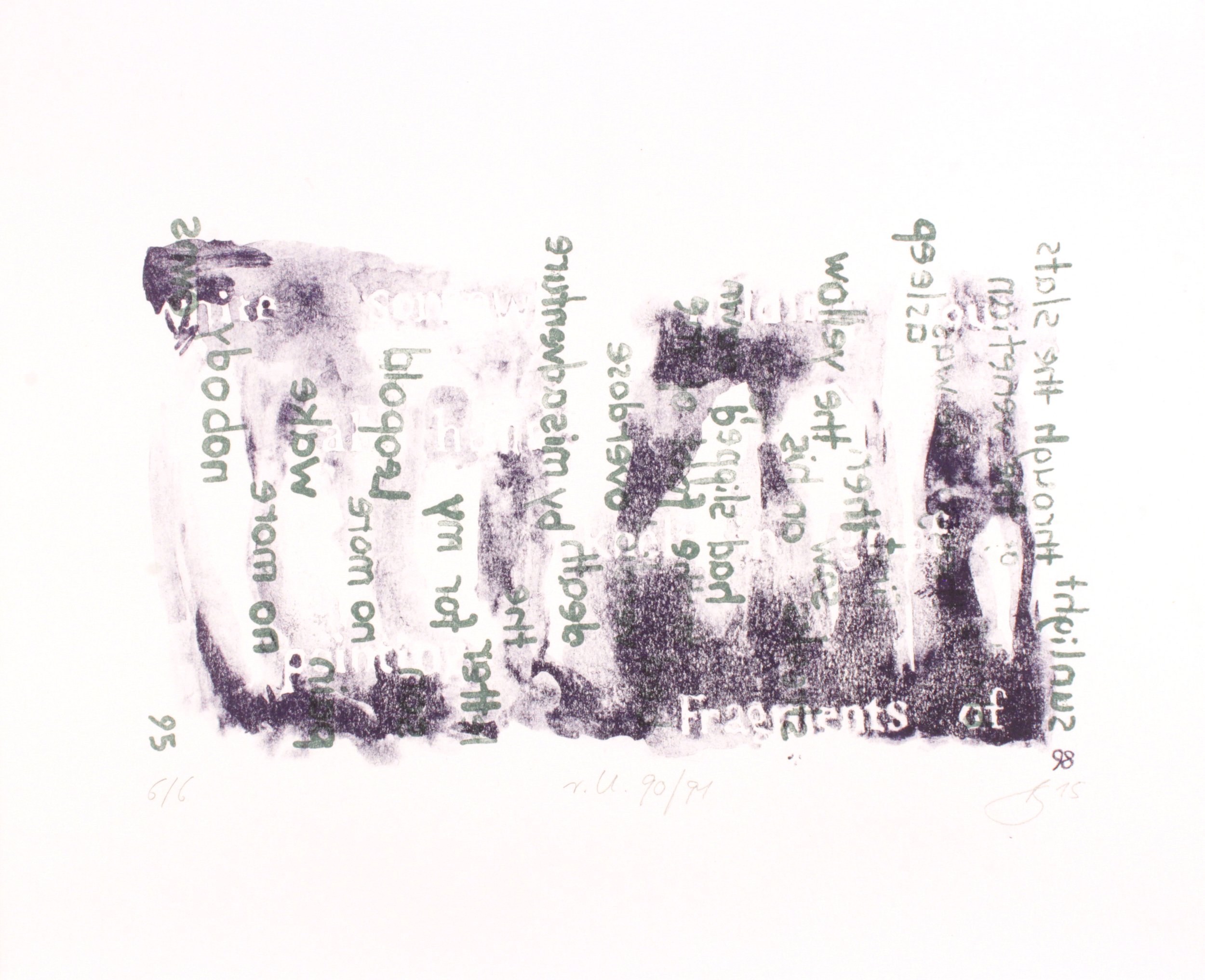

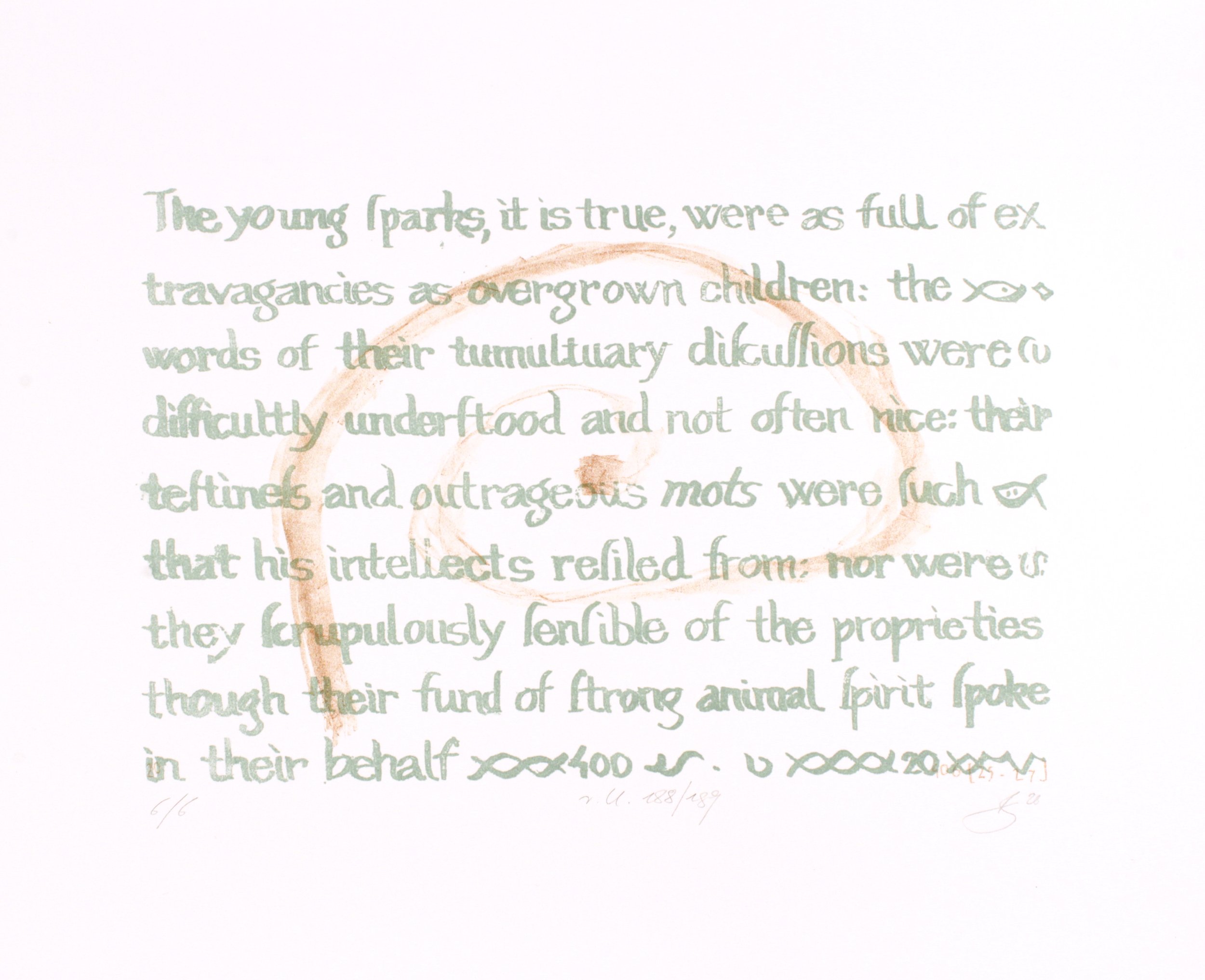

EPISODE 14

At the Maternity Hospital Bloom wants to check on a friend who is in labour. He does not get to see the lady but ends up in a room where a group of young men, Stephen among them, is passing time with drink and discussions about different aspects of maternity.

The episode is renowned for the succession of prose styles in chronological order which Joyce uses to draw a parallel between the ripening of a human being during pregnancy and the development of the English language.

The progression in language finds its analogy in a succession of historical script, starting with Gothic and Carolingian writing used for the medieval parts and ending with a sloppy scribbling which represents early 20th century slang.

Alternating with the texts images without text represent text passages of their own which you can find in the list.

EPISODE 15

What happens in Nighttown, Dublin’s red-light district, where Bloom has followed Stephen, cannot be summarized in just a few sentences. Alternating with scenes taking place in and outside Bella Cohen’s brothel, we see grand, phantasmagorical, nightmarish theatre, hallucinated either by Stephen or – mostly – Bloom and involving innumerable figures: practically the whole personnel of the novel, alive and dead, supplemented with historical or mythological personages and several crowds.

As classical illustration was out of the question, I relied entirely on symbolic images, inspired by arts history, early 20thcentury erotic photography, Japanese Shunga art, film, various religious contexts, and numerous other sources.

To create an overall dreamlike and sombre atmosphere, I chose black as the basic colour and, with a few exceptions, allowed the pictures to be chaotic with objects and figures emerging from fume-like scribbles. Only at the apparition of little Rudy in the last picture, I let the mists disperse.

EPISODE 16

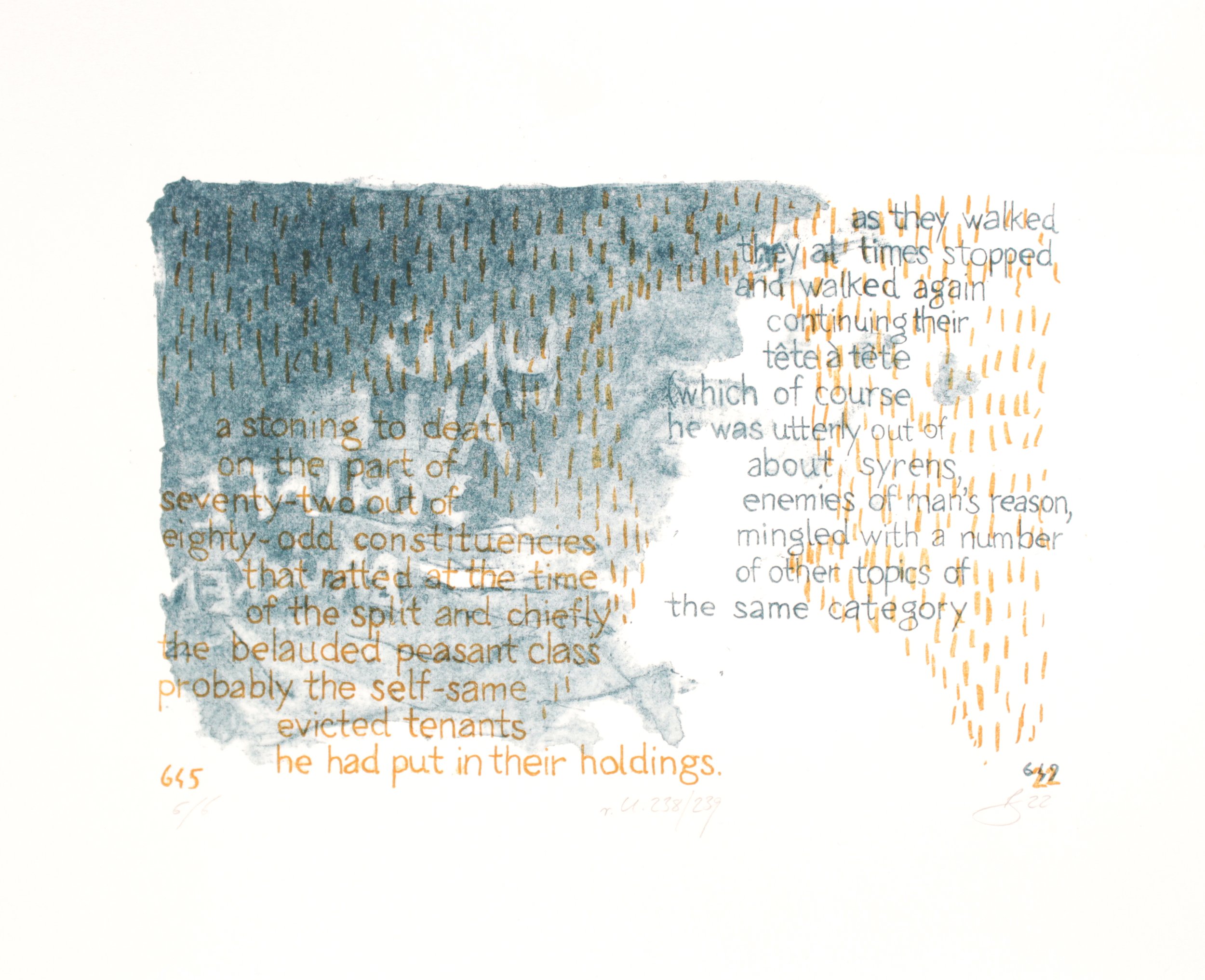

Stephen, owing to large quantities of alcohol and a punch in the face, needs some building up, so Bloom takes him to a cabman’s shelter. He tries to make him eat and drink and engages him in conversation, while the other customers are entertained by a drunken sailor. The episode largely has the appearance of talk for talk’s sake which Bloom employs partly to keep Stephen awake and get him back on his feet, partly to convey a cultivated image of himself.

I tried to capture the monotony and lengthiness of the episode with an arrangement pattern of image and text which is perpetually repeated, and by choosing a neutral, somewhat conventional script.

The images often do not refer to the text appearing in the picture but to passages surrounding it and so rather complement than illustrate it.

EPISODE 17

The story of Bloom’s return home together with Stephen, their final exchange over a cup of cocoa in the kitchen, Stephen’s departure und Bloom’s joining Molly in bed, is told in a series of questions and answers reminding strongly of a catechism. This very matter-of-fact form of presenting emotionally charged subjects in the costume of lists, registers, and pedantically exact descriptions, counteracts the traditional cliché of the hero returning home and works as an anti-climax.

My pictures treat this absurd relationship between form and content, which has a comical side, too, by combining a deliberately neutral lettering based on a classical sans serif font (abandoned only occasionally in favour of a humanist italic) with images, which, as a contrast, are executed as either vague and nebulous hatched structures, often (and sometimes wrongly) reminding of landscapes, or clear, simple, linear drawings which, however, don’t always seem to fit.

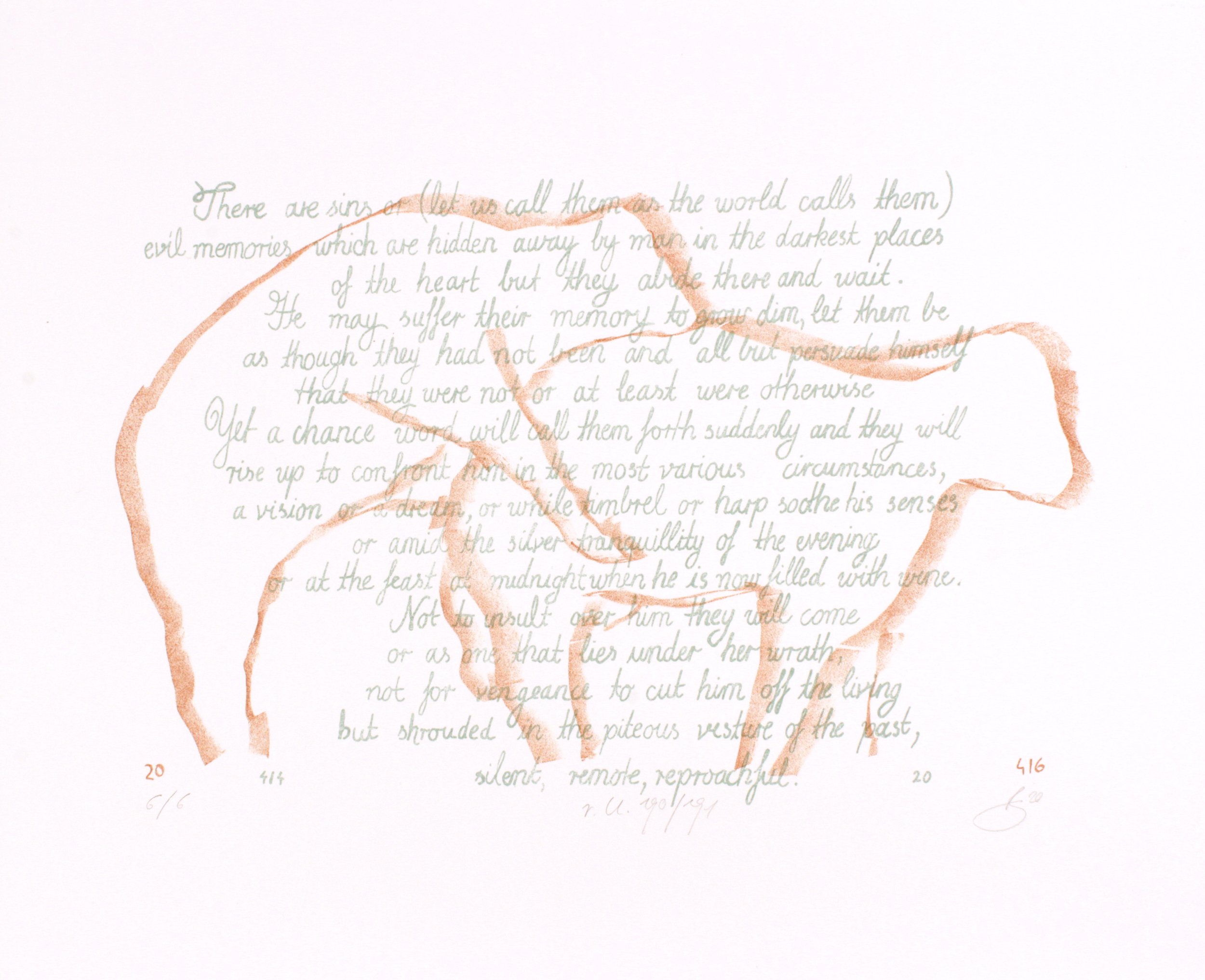

EPISODE 18

In a monologue of over 40 pages without interpunctuation, Molly Bloom, lying awake, tells her view of the story: her marriage, her affair with Boylan, her youth in Gibraltar, admirers and sweethearts, her views on men and women in general, her career as a singer which has not worked out the way she imagined, her daughter growing up and out of her reach, her son deceased as an infant.

We learn what she desires from life and what she thinks has gone wrong in hers, most of which she blames on her husband and his peculiar ways. Yet she is indignant at the way other men treat him, and finally, recalling the day when he proposed to her, she reaffirms her decision to marry him.

It was clear to me that what is going on in Molly’s head should be written in a hand of hers, which I had to invent. To get away from my own hand, I took 19th century English handwriting, reduced the slanting, and, writing side-inverted (which, writing on the printing stone, you must do anyway) practiced until I arrived at what could pass as the hand of a person not much concerned with calligraphy.

Along with thoughts and memories, physical sensations play an important part in this episode. This is why I introduced hints of lace, embroidery, the linen of a crumpled bedsheet and flower patterns to give a more material quality to the pictures. I like to imagine Molly’s thoughts influenced by what she is feeling on her skin, even as they veer to other places and times.